PASTORAL PILGRIMS

Faculty, staff, and students embrace hikes, history, poetry, and lots of English sheep to do reconnaissance for a reimagined Kiplin Hall study abroad program.

We woke up in strange beds, super early because the sun rises before five in summertime England, and discombobulated because our circadian clocks were still on American time—midnight. It was our first full day in the country, and we had woken up in Kiplin Eco Lodge, our accommodation for the trip. This was across the road from Kiplin Hall, the historical country house of the Calvert family before they crossed the Atlantic Ocean and founded Maryland.

That first day, we hiked Greenhead Ghyll—the setting of the William Wordsworth poem quoted above and the perfect place to immerse oneself in his poetry. The hike not only let us experience Wordsworth’s world, albeit centuries later, but also worked as a bonding experience for the group as everyone encouraged one another over the difficult terrain to reach the summit.

For 20 years, this very same Greenhead Ghyll hike was standard for the iconic Kiplin Hall trip, a three-week study abroad program conducted by English professor Richard Gillin and his wife Barbara. Every year, dozens of Washington students would travel to northern England—later trips included southern Ireland—to read Romantic literature where it was written and hike the landscapes described. They would stay at Kiplin Hall itself for the England portion—it no longer offers accommodation and is being converted into a welcome center.

“The fundamental idea was to go to those sites and have students read about an experience and then have their own experience in the same, or pretty close to the same, location,” Gillin said. “We wanted students to have a physical experience, as well as an emotional and intellectual event.”

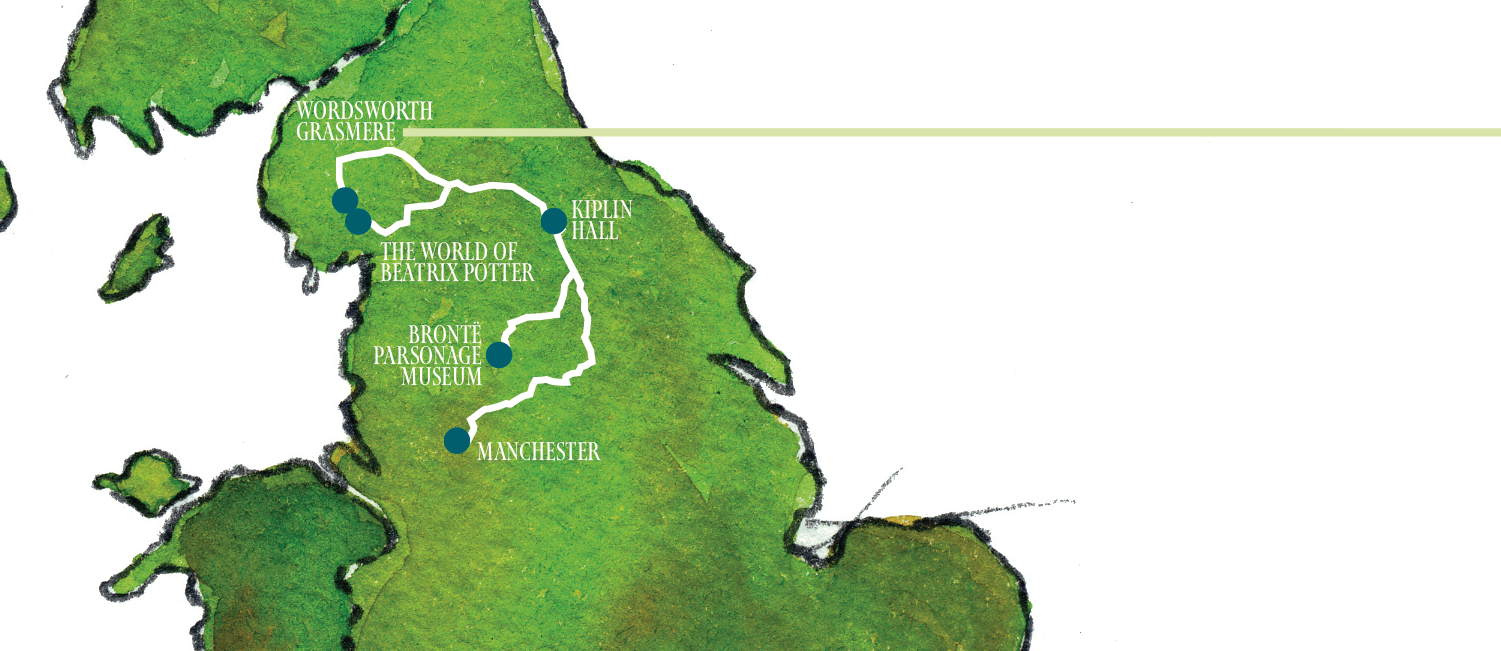

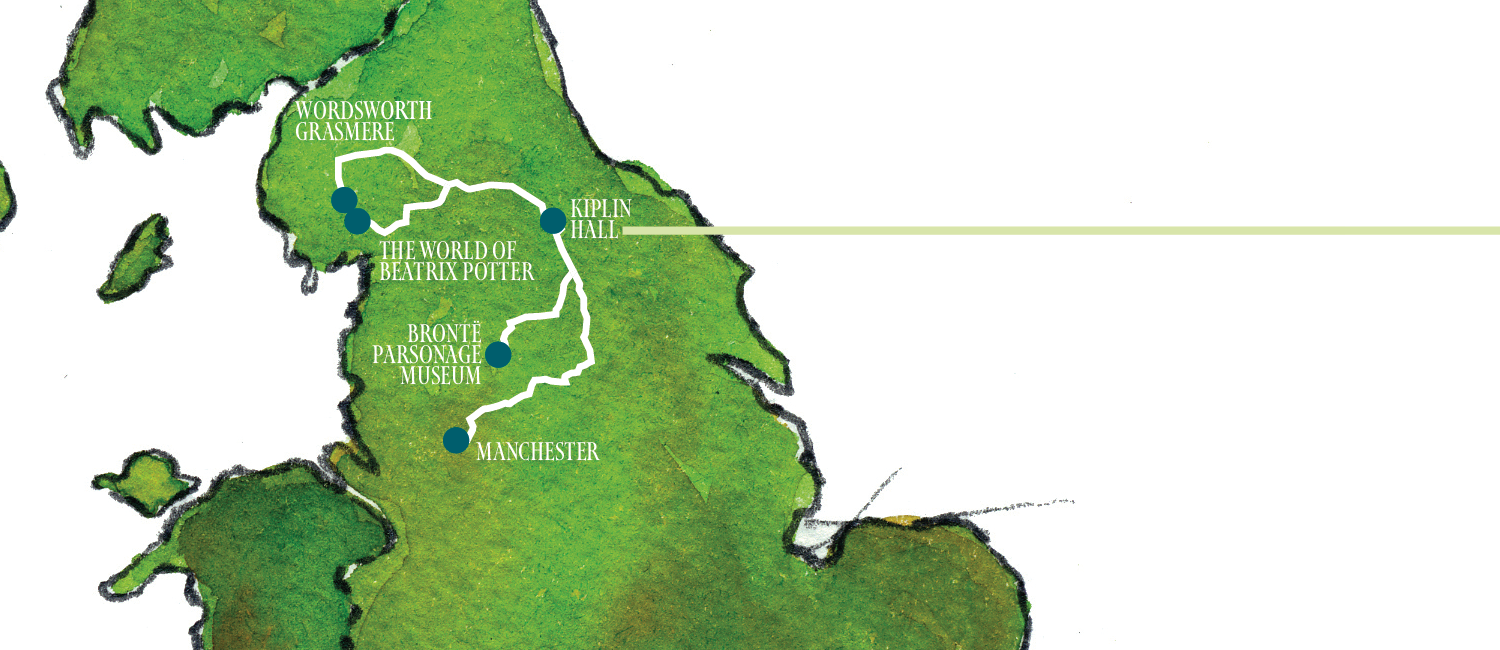

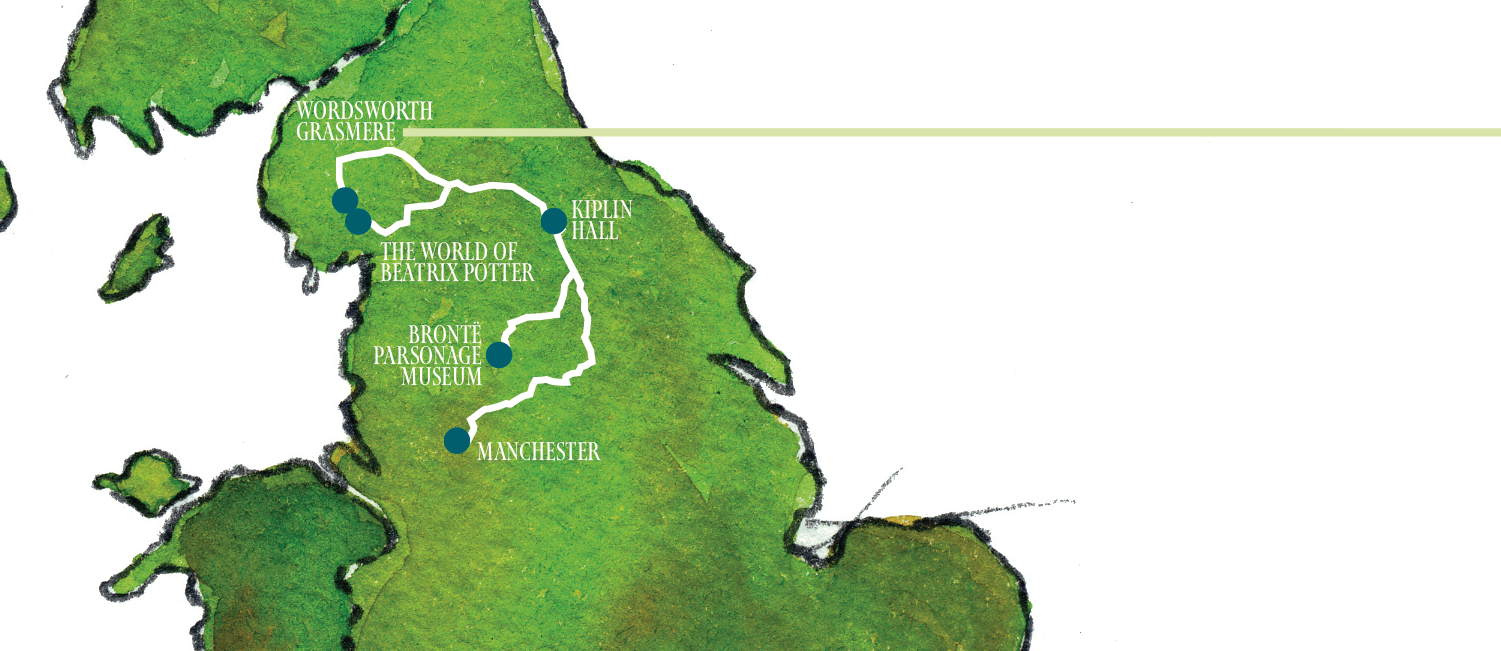

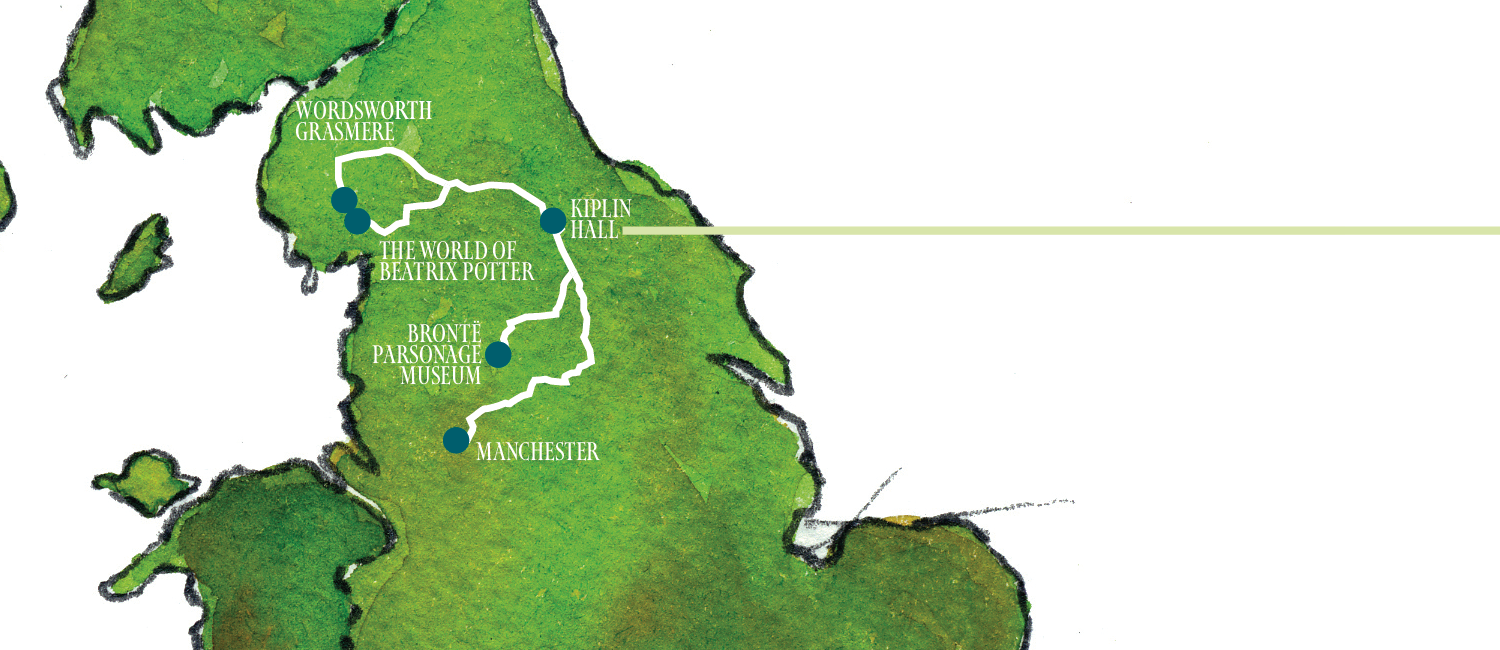

June 1-2:

Travel. Manchester to Kiplin Hall. Grocery shop. Eat breakfast for dinner.

June 3:

Lake District. Wordsworth Grasmere. Tea. Hike Greenhead Ghyll. The Farmers Arms for dinner.

June 4:

Lake District. Bowness-on-Windermere. Visit The World of Beatrix Potter Attraction, explore town, visit Storrs Hall. Hike Brant Fell Viewpoint. Tacos and quesadillas for dinner.

June 5:

The Yorkshire Moors. Drive to Haworth. Visit the Brontë Parsonage. Hike Penistone Hill Country Park. Explore town. Visit Middleham Castle. Pasta for dinner.

June 6:

Kiplin Hall. Tour the hall. Plant ferns in the Maryland Garden. Tea. Watch the filming of a documentary. Dinner at Kiplin Hall.

June 7:

Manchester. Train to Quarry Bank. Visit the mill. Train to Manchester. Stan m1 for dinner.

June 1-2:

Travel. Manchester to Kiplin Hall. Grocery shop. Eat breakfast for dinner.

June 3:

Lake District. Wordsworth Grasmere. Tea. Hike Greenhead Ghyll. The Farmers Arms for dinner.

June 4:

Lake District. Bowness-on-Windermere. Visit The World of Beatrix Potter Attraction, explore town, visit Storrs Hall. Hike Brant Fell Viewpoint. Tacos and quesadillas for dinner.

June 5:

The Yorkshire Moors. Drive to Haworth. Visit the Brontë Parsonage. Hike Penistone Hill Country Park. Explore town. Visit Middleham Castle. Pasta for dinner.

June 6:

Kiplin Hall. Tour the hall. Plant ferns in the Maryland Garden. Tea. Watch the filming of a documentary. Dinner at Kiplin Hall.

June 7:

Manchester. Train to Quarry Bank. Visit the mill. Train to Manchester. Stan m1 for dinner.

Setting the Pace

Before we ascended Greenhead Ghyll on that first full day, we read aloud stanzas of “Michael” on a grassy bridge, approximately where Wordsworth himself had written the poem. We learned that the beautiful purple flower covering the bridge was the poisonous foxglove and pipes crisscrossing the hills transported water from the area to the city of Manchester from our guide Jeff Cowton, principal curator and head of learning at Wordsworth Grasmere, an institution dedicated to the preservation of Wordsworth’s literature and of historic buildings in the town of Grasmere, where the poet made his home.

Typically, that would be the end of the hike with a Wordsworth Grasmere guide. However, Barnett-Woods asked Cowton if we could continue to the summit. Cowton got a sparkle in his eye and made some calls to his wife and the office to let them know he wouldn’t be back for a while, and we headed for the trail—a steep, rocky path.

“I remember looking up and not believing [we would hike to the top] because it seems insanely tall and being like, ‘Shoot, we all agreed, OK, we’re going up there,’” Osucha said.

Mel Tuerk '26, Beth Choate, and Halina Saydam '25 at Wordsworth Grasmere.

Mel Tuerk '26, Beth Choate, and Halina Saydam '25 at Wordsworth Grasmere.

The hike was a hard one. Not only because it was the group’s first but because, as Wordsworth wrote in “Michael,” “your feet must struggle; in such bold ascent.” Keeping with the spirit of Charles’ directive, we stopped often to catch our breath, drink water, sit down, and enjoy the views.

At the top, we did indeed come face to face with the pastoral mountains, as Wordsworth promised. We sat and took in the hills and valleys and watched the fog roll in, bringing a drizzling rain with it. Cowton read us another Wordsworth poem, and as he got to the part about sheep, the students squealed. Sheep, which had apparently been grazing around the other side of a cliff face, came into view, and the image Wordsworth created literally played out in front of us.

That moment, and the fact that the terrain changed from rocky and steep to grassy and winding, reinvigorated us. There were little watering holes where ducks swam. Sheep grazed around us, often stopping to stare at us. Monteleone collected loose sheep wool along the trail. The atmosphere, literally and metaphorically, had shifted to a gentler, more reflective one, and the connections to Wordsworth’s writing had become abundantly clear.

Expanding the Kiplin Hall Community

Under Charles, the reimagined Kiplin Hall Program will draw clear connections between literature, writing, history, and the environment. The goals of the fact-finding trip, which may also shape the objectives of the new program, were to engage with literature and travel writing, understand transatlantic historical connections, and observe environmental contexts and the interactions between human and non-human worlds.

“I see this as an opportunity to amplify parts of the trip that were already or always present in a really embodied way,” Charles said. “Rich and Barbara Gillin ran this program as two people doing the work of a village of people. Recognizing I would not be able to shoulder that work on my own, I started looking around for the natural collaborators.”

Being a historical literature scholar herself, wanting to keep the Gillins’ robust writing component and add environmental and humanities components, Charles said it wasn’t a leap to think of collaborating with the three centers of excellence.

To prepare for the trip, everyone received a reading packet of material from the various disciplines to contextualize sites and provide background for discussions. During the trip, all participants kept journals to reflect on the activities, discussions, and readings of each day. After the trip was over, students were tasked with choosing a topic from the trip and researching how it could be explored more on a future trip.

In addition to being a rehearsal for how an interdisciplinary program might work in practice, Charles conceptualized this year’s trip as an opportunity to “train the trainers,” letting faculty explore and make connections to the sites ahead of a full-length program beginning in 2025.

Quinn Hammon '26, Mel Tuerk '26, Kaitlin Osucha '25, Annabella Goglia '27, Halina Saydam '25, and Logan Monteleone '27 pose with Flat Gus at Middleham castle.

Quinn Hammon '26, Mel Tuerk '26, Kaitlin Osucha '25, Annabella Goglia '27, Halina Saydam '25, and Logan Monteleone '27 pose with Flat Gus at Middleham castle.

Quinn Hammon '26 sketches before hiking Greenhead Gill.

Quinn Hammon '26 sketches before hiking Greenhead Gill.

A Very Full Week of Exploration

Because a three-week program was to be condensed into a little over a week, our exploratory trip was a sprint from the start—like an academic version of a reality TV race to cover as much intellectual terrain as possible in ten days. We arrived at Kiplin Eco Lodge with only 30 minutes before the grocery store closed. We broke off into teams of two to take assigned lists to make sure we had all the food we’d need for the week.

Each day, the 11 of us piled into two vans driven by Choate and Barnett-Woods, and went to different literary, historic, or environmental destinations, each within a two-hour drive of Kiplin Hall. We used the long drives to read assigned readings aloud, help navigate driving on the “wrong” side of the road, discuss interests outside of those that brought us to England, contextualize the day’s events, and more. Meals were eaten together and cooked communally by the students.

Anyone who experienced the original Kiplin Hall trips might recognize some of these classic elements, which originated from the Gillins’ belief that fostering connections and community among the participants was a vital aspect of the experience. While our destinations and purpose varied every day, the trips followed a similar pattern: wake up, drive, explore the destination (often with a guide), discuss literary, historical, and environmental elements of the place, and provide context to the environments we were experiencing, hike (or some other outdoor activity), take time to consider the space we were in, explore the town, drive home, make dinner, eat, sleep.

The day we hiked Greenhead Ghyll started at Wordsworth Grasmere, where we explored Dove Cottage—the home of Wordsworth, his wife and children, and his sister Dorothy. It was pretty dark inside and Osucha explored it by candlelight. Goglia stayed in what was a gathering room to draw and write in her journal, likely in the very spot where Dorothy Wordsworth would have written.

“There are many moments I continue to come back to,” Tuerk said. “One of them is eating lunch in the garden at the Wordsworths’ Dove Cottage. Sitting amongst friends in the space that poets did so many years ago was really unique, and then after that, the hike we took on Greenhead Ghyll while reading Wordsworth’s poetry was the cherry on top.”

We took a workshop on paper making, printmaking, and bookbinding—complete with a how-to-fold-a-leaflet tutorial—before exploring the Wordsworth siblings’ original texts. We read poems aloud—Monteleone even read from a first edition of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Christabel,” which she called “unforgettable”—and in groups of three, tried transcribing William Wordsworth’s draft of “Michael,” handwritten in the margins of a re-bound Coleridge poem, and two of Dorothy Wordsworth’s handwritten journals.

While one day was more literature-focused, another would have a more historical bent, while another still would literally dig into the environment. There were many shining moments when the discussion flowed naturally between disciplines and exemplified the interconnectedness of everything.

The second day was the perfect example. After spending the morning at The World of Beatrix Potter Attraction talking about conservation, preservation, consumption, and consumerism, we spent some time exploring Bowness-on-Windermere before going to Storrs Hall, a luxury hotel now that in the 1800s was home to infamous slave trader John Bolton. It was cold and rainy, so our group wandered the grounds, heading to the Temple of Heroes located on the property. There, we dived into a conversation about the interconnectedness of slavery and capitalism and the presentation of the histories of the places we’d visited and the people that made them what they are today.

Sitting amongst friends in the space that poets did so many years ago was really unique, and ... Greenhead Ghyll while reading Wordsworth’s poetry was the cherry on top.

MEL TUERK '26

“Though it was gloomy and windy, and we were zipped up to the chin in raincoats, standing there in a circle in the open air, the amount of attention we gave one another and the level of reflection everyone offered to the conversation that Dr. Barnett-Woods facilitated about the suppression of complicated histories and immoral historical figures was profound,” Monteleone said.

That afternoon, the weather cleared up in time for a hike to Brent Fell Viewpoint. On the side of the hill, Kesey spoke about travel writing and wandering into the unknown. We climbed the rocks at the top and took in the view of the lakes and the expansive landscape below. Students collected wildflowers for a bouquet or to put in their hair, then frolicked (their word) along and rolled down the hills.

“Looking over at each other smiling and shouting as we climbed over rocks, stood on precipices with outstretched arms, tumbled down hills, and sat among wind-blown heather in the moors created this profound sense of shared joy, beauty and experience I don’t think I’ll ever forget,” Monteleone said.

On day three, we traveled to the Yorkshire moors—home, and landscape for the Brontë sisters—and sat among the wind-blown heather where the sisters would have sat. We took a guided hike with Stuart Davies from the Brontë Parsonage Museum, which we had explored in the morning, to learn more about the family of writers, their father and brother, and the history of their land and town.

“As far as environmental spaces go, I’m interested in human connection to them and the connection to history,” Goglia said. “To see just how close the Brontës were living to the environment that inspired them, that’s a cool connection there. I thought for sure the moors were going to be this big, sprawling something, and it was just like the easiest hike we took the whole week. They were just right there.”

At the top of the moors, Davies read us a few poems before heading back to the parsonage. We stayed on the hill, and Kesey led the students in a writing exercise, making them separate and describe what they were experiencing. Many of them wrote poems.

“When people ask about my favorite part of the trip, I immediately think of our writing activity on the moors,” Saydam said. “Feeling the wind shoot through my hair and howl through the heather felt so central to the landscape.”

Osucha’s experience on the moors was less physical and more internal. “You’re out in nature, but you were also kind of alone. Knowing that there were people nearby, but you also had a sense of being by yourself, was pretty cool. It was an emotional moment.”

After we came back together, Choate talked about the layers of the brush we were standing on and what that ecosystem was doing for the environment, particularly in absorbing carbon. She pointed out spittlebugs, hidden under the little white bubbles in the grasses, and students felt the different textures of the plants and smelled some of them growing there.

Sitting on the hill to write “gave me time to be more curious about the minute details of the plants and bugs and terrain in the area. When we regrouped, it was really exciting to learn from Dr. Choate about the things I had observed when I was by myself,” Hammon said. “I loved moments like that where I felt so close to the environment or to history that I was suddenly interested to learn about something I had never thought to be curious about before.”

After two days in the lake district and one at the moors, we explored Kiplin Hall itself.

Goodheart led a discussion on the grounds overlooking the lake, introducing the historical context before we explored the hall itself. Inside, volunteers told us about the structure’s history, the four families that owned it over its 400 years, and some of the artifacts housed in each room—on loan from descendants of those families.

Kiplin Hall staff are currently working on a project to expand the narrative of the families that owned the building. While we were there, they were working on a Maryland garden to showcase some of the plants the Calverts would have found when they arrived in Maryland. Several of the students were excited to help with the planting in the garden and fully embraced the project after environmental science major Saydam confirmed with staff that none of the ferns they would be planting would be invasive to England.

Griswold, still actively engaged in the program, joined us at Kiplin Hall. We discussed the Calverts, Maryland, and our experiences at Washington College. He then invited us to the set of a documentary he is helping produce on the Calvert family, where we watched two scenes being filmed. Griswold’s ongoing, generous support of the program and commitment to honoring the Gillins’ legacy led him to found and contribute to the Barbara Gillin Scholarship Fund, which will support students on future trips and is committed to making them accessible to all interested students.

In our last full day in England, we traveled by train to Quarry Bank, a textile factory from the Industrial Revolution that processes raw cotton into cloth. We explored the grounds there, visiting the company homes, churches, and the grocery store that employees and their families would have used. We learned about the machines and histories of the children working in the mill and witnessed some of the work conditions. The stairs were well-worn below our feet, the floors vibrated when the machines were turned on, and the noise and speed at which the machines ran were overwhelming.

We ended the trip in Manchester to experience urban England, with a directive to look out for wild spaces in the city. The differences between the rural and urban, industry and agriculture, inspired many of the students’ final projects.

Students’ Feedback Will Inform the New Program

“We spent so much of our time on the trip discussing how the English landscape impacted the writing of British authors but didn’t touch much on how the landscape has changed over time,” Saydam said. “It is interesting to see how different writers view their spaces and how they have influenced their stories.”

Tuerk said a comprehensive study of the local communities and changing environments would be a good inclusion for future trips. “I think it is good traveling practice to learn about the place you are visiting and the details of daily life and activities there and consider all of our studies in the context of the local community.”

While on the trip, and to expand their experience of the landscapes they were immersed in, several of the students kept visual journals alongside their written ones.

“Sketching and writing feel like a way to ground myself and know that I’m absorbing the experience,” Hammon said. “It helps me get a more intimate understanding.”

The journals, final projects, and feedback forms that the students submitted will serve as data points of what resonated with students to guide the trip leaders as they plan next year’s itinerary.

Charles noted that while the literary and embodied aspects of a Kiplin Hall study abroad were well-developed over the Gillins’ many trips, the thoughts shared by the students on the new interdisciplinary topics and activities will be vital in fine-tuning how to work in more of the science, history, and creative writing elements going forward.

The Future of Washington College’s Kiplin Hall Program

Only time will tell how this year’s exploratory mission will shape the future of the Kiplin Hall program and what comes next, but it is clear that, in line with the trip’s legacy, participants formed connections with one another and the nature around them in ways they will continue to think about.

“Many people during the Kiplin years would ask me why

we would spend so much time pacing around northern

England and southern Ireland with groups of undergraduates,” Gillin said. “It was love. The love between Barbara and myself, the love of the various landscapes, and the love of teaching informed our commitment to the program.”

Throughout their tenure, the Gillins would intentionally seek out new places to connect to literature for future trips. They would also tailor specific itineraries based on the students in attendance. When it was time for Gillin to pass the gauntlet to Charles, he told her not to feel obligated to reproduce what he and Barbara had done.

“That was our take on it; that was our view of how the program should work and what we were willing or able or wanted to do,” Gillin said. “I’m happy with the configuration that is there now. It opens it up in a different way to other students,” he said of the new interdisciplinary conception of the program.

Charles said it was talking with Kiplin Hall trip alumni that convinced her to take over the program to continue the Gillins’ legacy of profound impacts on decades of students. She said that nearly everyone she spoke with referred to the trip using language and metaphors for transformation, saying it had changed them and often represented an “encapsulation of their liberal arts education.”

“One of the things that made this trip such a glorious success in the past is that the experience felt so deeply personal and unique to each student,” Charles said. “You can’t be prescriptive in a way that somehow guarantees that, but you can try to build a course that’s designed to foster that kind of individual curiosity that’s also building on past student experiences and faculty experience.”