Photographing Pollinators

Campus photographer Pamela Cowart-Rickman discovered that Washington College supports a rare and important population of native ground-nesting bees.

Like falling down Alice’s rabbit hole, you never know what you will find when you take a closer look at the natural world. Although I have a degree in biology, I didn’t become interested in insects until much later when I took a course on dragonflies while working at Washington College. That course immediately lit a fire in me. I started photographing dragonflies and damselflies, which evolved into cataloging insects on the College’s main campus, the River and Field Campus, and beyond.

I was surprised by how many unknown and unrecorded species there still are in the insect world and how little information is actually known about certain species. During the Covid lockdown, Dan Small with the College’s Natural Lands Project encouraged me to get involved with iNaturalist and the Maryland Biodiversity Project.

Now, I devote a lot of my free time to being a citizen naturalist, and through my photography, I have helped researchers identify and track insect populations. I’ve photographed and collected rare or undocumented species for Maryland Biodiversity, BugGuide, iNaturalist, and researchers at the Canadian National Collection of Insects. I’ve become particularly interested in insects as indicators of biome health.

Before this, in 2018, Washington College had become one of the early Bee Campus USA partners. Bee Campus USA brings college communities together to sustain pollinators by increasing the abundance of native plants, providing nesting sites, and reducing the use of pesticides. When the College signed onto the program, we had no idea that we had an important native bee population nesting literally under our feet.

When people think of saving bees, they think of the honeybee, which is a non-native livestock species introduced from Eurasia and not threatened. When you introduce a hive of non-native bees, they can actually hurt the native bee populations by introducing disease and competition. The native bee populations are diverse and perfectly compatible with the fruit trees and plants that grow in North America and are capable of pollinating better than a honeybee.

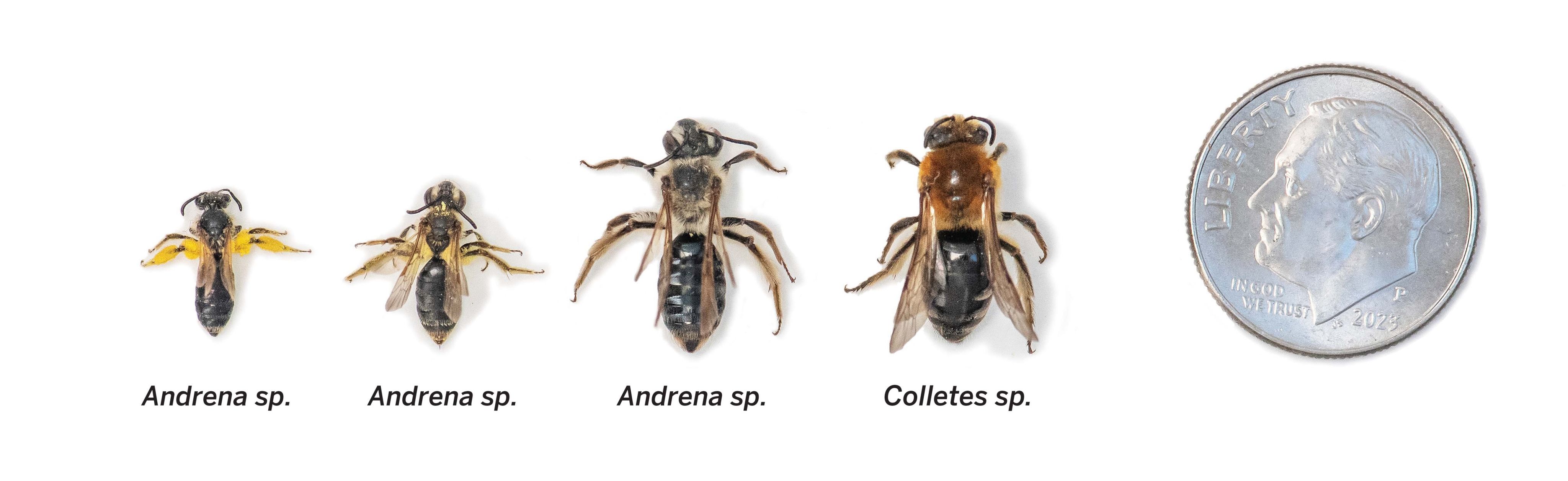

A couple of years ago, College grounds manager Mallory Westlund and I noticed native ground-nesting bee activity on the hill outside Middle and East Halls every spring. I began investigating and photographing them to satisfy our joint curiosity and realized there were at least two different species, Andrena and Colletes, nesting in the same area. I uploaded my observations to iNaturalist, an international research database. It appears these native bees had been nesting here for years, maybe even decades.

The Andrena start emerging in early spring. You’ll see the ground starting to be turned up, the red soil coming to the surface a lot like what earthworms do when they aerate the soil. That’s about all you’ll notice of the Andrena themselves unless you look really close to see them going in and out of their solitary nest holes.

Then, in May, when the Colletes begin emerging in a small section of the Andrena territory, you’ll see the male Colletes flying furiously back and forth low over the ground, waiting for the females to emerge. You can stand there amongst them and they ignore you. The male Colletes are so fixated on finding a female, and the females are so focused on digging their nests and setting their eggs that you can sit amongst them and watch them unnoticed. They bounce off you; they land on you; and they are very gentle, very peaceful. It’s just an amazing experience.

I would never attempt that with wasps, hornets, or any hive-nesting bees like honeybees or bumblebees. The native ground-nesting bees are very tolerant of the normal campus activity around them; students walking back and forth to classes and groundskeepers mowing the grass do little to phase them.

After seeing one of my bee photos on iNaturalist and realizing the rarity of the site, Jordan Kueneman, a researcher with Project GNBee who is working on tracking ground-nesting bees at the Danforth Lab at Cornell University, reached out to me about possibly providing further research samples and adding Washington College to their research project. Kueneman was excited by the size of the aggregation and that multiple species are utilizing the same area, stating that “ground-nesting bees are a vital and overlooked group of pollinators essential to terrestrial ecosystems.”

I took a much closer look at the bees nesting in the aggregation. I had already identified Andrena and Colletes nesting there, with several Nomada bees that were parasitizing those bees, but when I started looking closer, I noticed there was potentially a greater variety using the same site than I had ever imagined. I collected several samples of the bees and went over to see Sam Droege at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Bee Lab near Bowie, Maryland. Droege was very gracious and sat down and looked at what I had brought him. He identified several different Andrena species, bringing our tentative total of nesting species on the same site to five.

Droege made a wonderful observation, “The Washington College site provides rare nesting habitat for multiple native bee species, several of which are uncommon and unidentified. We always talk about providing plants to support native bees and other pollinators, but we rarely think about providing adequate nesting habitat for their survival.” Droege’s statement really struck me because he is so right. We don’t think about complete life cycle support, just the part that easily benefits us.

Kueneman hopes that the Washington College aggregation will provide the opportunity for students and the public to learn about the biology of ground-nesting bees and the value they provide to the environment. Along those lines, in partnership with Cornell’s Project GNBee and the USGS Bee Lab, we plan to do a complete assessment of the aggregation next spring. I’ve spoken with Washington College Center for Environment and Society Deputy Director Beth Choate, who has a degree in entomology, about involving students in the project as well. Washington College has been given a great opportunity to not only preserve a valuable native bee nursery, but also to provide a unique native bee educational experience.

Pamela Cowart-Rickman

Pamela Cowart-Rickman

A female Colletes emerges from her ground nest.

A female Colletes emerges from her ground nest.

A female Andrena foraging on campus flowers.

A female Andrena foraging on campus flowers.