Reconfiguring Worlds

Blending art and science, Deborah Anzinger ’01, Ph.D., reimagines our relationship to the land, the body, and history.

Deborah Anzinger ’01 is an interdisciplinary artist whose work spans painting, sculpture, video, and sound. Through her wide-ranging practice, she explores how we perceive and relate to people and the land around us. Drawing on her background in both the arts and sciences, Anzinger is particularly interested in how history—especially colonialism and capitalism—has shaped our understanding of race, gender, and nature. Her work poses questions about those systems and attempts to imagine more equitable ways of seeing and being in the world.

Anzinger grew up in the parish of Saint Andrew, Kingston, Jamaica. “I first developed an interest in art, I think probably from the moment I could hold a writing implement,” she said. “I’ve always been interested in making things and in making pictures too.” Her mother, who had briefly studied art in New York, was one of her earliest influences. “Most of the time that I can actually remember where we were doing anything recreationally together... it was usually art,” she recalled.

Untitled Transmutation 15, 2023, Ground local cookshop charcoal on paper, 65.6 cm x 63.8

Untitled Transmutation 15, 2023, Ground local cookshop charcoal on paper, 65.6 cm x 63.8

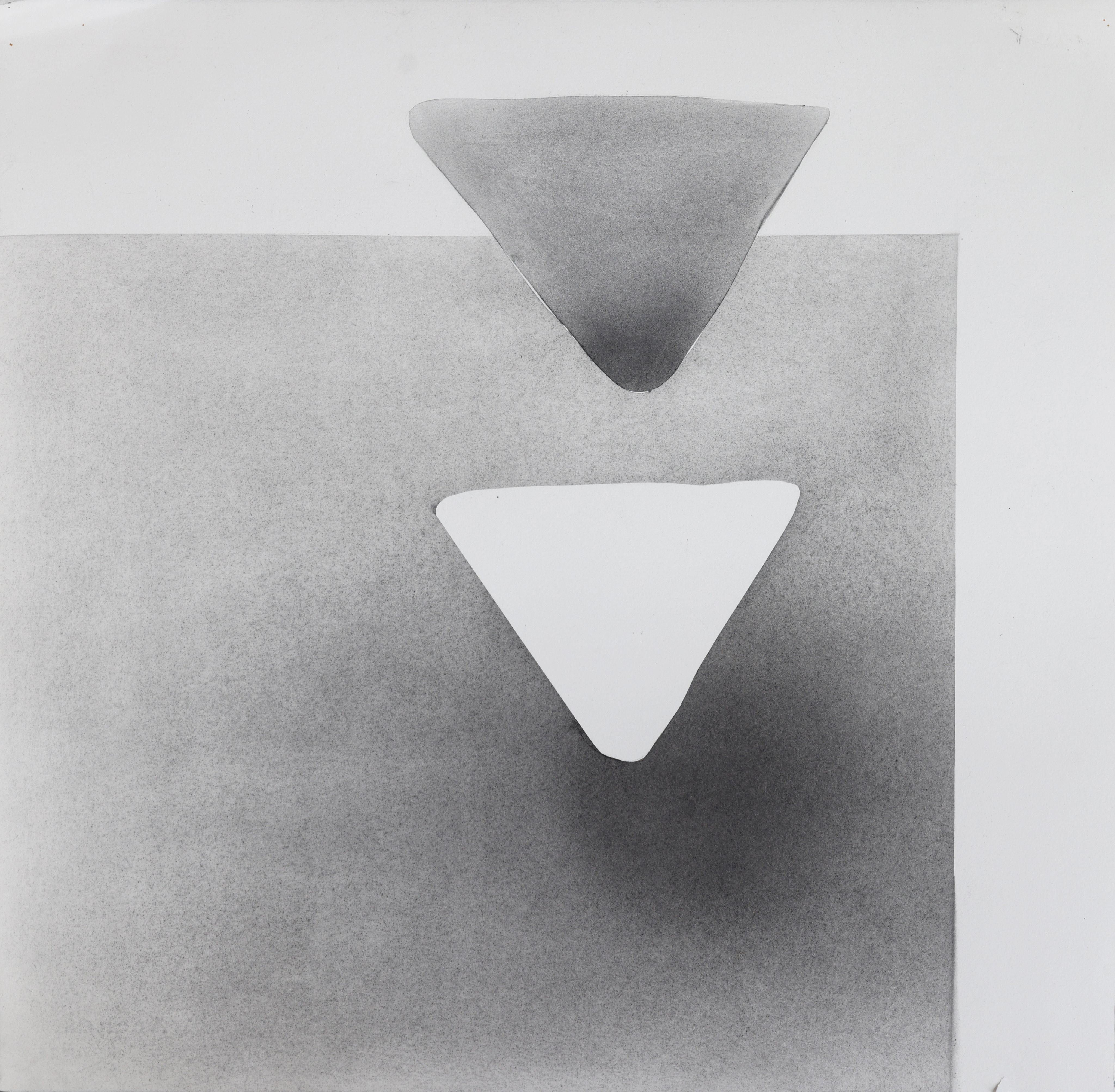

Untitled Transmutation 04, 2023, Ground local cookshop charcoal on paper, 57.2 cm x 57.2

Untitled Transmutation 04, 2023, Ground local cookshop charcoal on paper, 57.2 cm x 57.2

At the same time, Anzinger excelled in science throughout primary and secondary school. “Science was pushed more as a way to ensure livelihood and security,” she said. This duality—creative expression and scientific inquiry—continued to shape her academic and artistic development.

Anzinger attended Campion College, a top high school in Jamaica, and then enrolled at the University of the West Indies. But her plans shifted when her best friend, Gillian Hue ’00, who was enrolled at Washington College, introduced her to the concept of a liberal arts education. The ability to explore multiple disciplines simultaneously appealed to Anzinger, who ultimately transferred to Washington after a year at the University of the West Indies.

“I was able to do all the things: study world religions; I studied visual art with [art professor] Sue Tessem—that was great—I kept up with the sciences and had a really, wonderful experience with [biology professor] Rosemary Ford and learning genetics and plant physiology there,” said Anzinger. “And, truth be told, within my art practice, I do believe that my experiences with Rosemary Ford and plant physiology and [biology professor] Douglas Darnowski and all that I learned in terms of plants” still resonates.

Anzinger received a bachelor’s degree in biology with a concentration in plant physiology from Washington College and entered Rush Medical College in Chicago, where she earned a doctorate in immunology and microbiology in 2006. Following her doctoral program, she worked briefly at a non-profit art gallery in Washington, D.C., before shifting to pursuing art full-time.

Today, Anzinger’s work is grounded in both the U.S. and Jamaica, and she maintains studios in both countries, splitting her time between them. In Jamaica, she is a prominent voice in the art community, where she founded and runs New Local Space, a nonprofit contemporary art space in Kingston that supports local, regional, and international artists. She also serves on the board of the National Gallery of Jamaica and on the international advisory board for the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development.

Her aesthetic is rooted in abstraction, although it remains fluid and open-ended. “I find that abstraction can be a vital way of expressing an openness, a fluidity, a sort of dynamism in that nothing is ever quite fully identifiable or fully knowable,” she explained.

Her current body of work, Untitled Transmutation, is a series of monochromatic paintings on paper created using charcoal salvaged from a 2024 forest fire on ancestral land in Jamaica. This family land is home to a small farm and reforestation project and also serves as the location for Anzinger’s studio.

Coy, 2016 acrylic, Styrofoam and live Aloe Vera, mirrored plexiglass on canvas, 54" x 72"

Fiction as a vessel for reality, acrylic, Aloe Vera, ceramic, 2016

At the same time, Anzinger excelled in science throughout primary and secondary school. “Science was pushed more as a way to ensure livelihood and security,” she said. This duality—creative expression and scientific inquiry—continued to shape her academic and artistic development.

Anzinger attended Campion College, a top high school in Jamaica, and then enrolled at the University of the West Indies. But her plans shifted when her best friend, Gillian Hue ’00, who was enrolled at Washington College, introduced her to the concept of a liberal arts education. The ability to explore multiple disciplines simultaneously appealed to Anzinger, who ultimately transferred to Washington after a year at the University of the West Indies.

“I was able to do all the things: study world religions; I studied visual art with [art professor] Sue Tessem—that was great—I kept up with the sciences and had a really, wonderful experience with [biology professor] Rosemary Ford and learning genetics and plant physiology there,” said Anzinger. “And, truth be told, within my art practice, I do believe that my experiences with Rosemary Ford and plant physiology and [biology professor] Douglas Darnowski and all that I learned in terms of plants” still resonates.

Anzinger received a bachelor’s degree in biology with a concentration in plant physiology from Washington College and entered Rush Medical College in Chicago, where she earned a doctorate in immunology and microbiology in 2006. Following her doctoral program, she worked briefly at a non-profit art gallery in Washington, D.C., before shifting to pursuing art full-time.

Today, Anzinger’s work is grounded in both the U.S. and Jamaica, and she maintains studios in both countries, splitting her time between them. In Jamaica, she is a prominent voice in the art community, where she founded and runs New Local Space (NLS), a nonprofit contemporary art space in Kingston that supports local, regional, and international artists. She also serves on the board of the National Gallery of Jamaica and on the international advisory board for the Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development.

Her aesthetic is rooted in abstraction, although it remains fluid and open-ended. “I find that abstraction can be a vital way of expressing an openness, a fluidity, a sort of dynamism in that nothing is ever quite fully identifiable or fully knowable,” she explained.

Her current body of work, Untitled Transmutation, is a series of monochromatic paintings on paper created using charcoal salvaged from a 2024 forest fire on ancestral land in Jamaica. This family land is home to a small farm and reforestation project and also serves as the location for Anzinger’s studio.

Untitled Transmutation 15, 2023, Ground local cookshop charcoal on paper, 65.6 cm x 63.8

Untitled Transmutation 15, 2023, Ground local cookshop charcoal on paper, 65.6 cm x 63.8

Untitled Transmutation 04, 2023, Ground local cookshop charcoal on paper, 57.2 cm x 57.2

Untitled Transmutation 04, 2023, Ground local cookshop charcoal on paper, 57.2 cm x 57.2

Coy, 2016 acrylic, Styrofoam and live Aloe Vera, mirrored plexiglass on canvas, 54" x 72"

Fiction as a vessel for reality, acrylic, Aloe Vera, ceramic, 2016

These works reflect a circular relationship with the land—what Anzinger calls a “circular economy of reciprocity.” The charcoal, the result of devastation, becomes a material capable of spurring new growth while becoming a medium for documenting transformation and survival. “These paintings are a way of appreciating the value of the land... and the ecosystem that [the trees] provide for us,” she said.

In Untitled Transmutation, symbolic forms appear and reappear. “Often in these paintings you find that a symbol could, in one instance, be representing the landscape and that that same symbol in another instance might be representing part of the human body,” Anzinger explained. “In another instance, it might be representing a whole other type of body, a whole other type of species, if you will.”

Through this kind of visual fluidity, she removes boundaries—between the human and nonhuman, between anatomy and environment—emphasizing individuals’ and ecosystems’ constant state of change. “The body itself and the limits of the body also are in a constant flux—where does the body start and where does a body end?” she asked. Her work reflects a worldview in which forms are not fixed, but rather are always transitioning and always interconnected.

Anzinger’s work has been shown at institutions including the National Art Gallery of the Bahamas, National Gallery of Jamaica, Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (MoCADA) in Brooklyn, New York, Pérez Art Museum Miami, and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia (ICA Philadelphia). Her practice remains interdisciplinary, exploratory, and deeply invested in ecological and social transformation. See more of Anzinger’s work at deborahanzinger.com.

—Brian Speer

Often in these paintings you find that a symbol could, in one instance, be representing the landscape and that that same symbol in another instance might be representing part of the human body

Often in these paintings you find that a symbol could, in one instance, be representing the landscape and that that same symbol in another instance might be representing part of the human body

These works reflect a circular relationship with the land—what Anzinger calls a “circular economy of reciprocity.” The charcoal, the result of devastation, becomes a material capable of spurring new growth while becoming a medium for documenting transformation and survival. “These paintings are a way of appreciating the value of the land... and the ecosystem that [the trees] provide for us,” she said.

In Untitled Transmutation, symbolic forms appear and reappear. “Often in these paintings you find that a symbol could, in one instance, be representing the landscape and that that same symbol in another instance might be representing part of the human body,” Anzinger explained. “In another instance, it might be representing a whole other type of body, a whole other type of species, if you will.”

Through this kind of visual fluidity, she removes boundaries—between the human and nonhuman, between anatomy and environment—emphasizing individuals’ and ecosystems’ constant state of change. “The body itself and the limits of the body also are in a constant flux—where does the body start and where does a body end?” she asked. Her work reflects a worldview in which forms are not fixed, but rather are always transitioning and always interconnected.

Anzinger’s work has been shown at institutions including the National Art Gallery of the Bahamas, National Gallery of Jamaica, Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts (MoCADA) in Brooklyn, New York, Pérez Art Museum Miami, and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia (ICA Philadelphia). Her practice remains interdisciplinary, exploratory, and deeply invested in ecological and social transformation. See more of Anzinger’s work at deborahanzinger.com.

—Brian Speer